The term foot rot or “hoof rot” is one that might be used on your farm to describe a sore foot. Before explaining the disorder itself, let’s first check whether Google can shed some light on the definition. Actually, none can be found when using “hoof rot” to refer to cattle. Rather, this term is commonly used to describe an infection of the hoof in sheep, goats, and horses.

Foot rot is affecting a cow’s performance because of severe, acute pain in one leg. The cow usually has a fever and feed intake is down. Veterinarian’s service is often needed to prescribe an antibiotic treatment.

Interestingly, the terms used to describe “hoof rot” in cattle are “foot rot” and “foul-in-the-foot.”

To be clear, we will use the term “foot rot” in this post, and also refer to its scientific name, Interdigital necrobacillosis. However, we must be careful to not use this name to describe all lameness or different clinical pictures. This disorder is actually not a disease of the claw directly, but affects the subcutaneous tissue near the claw, particularly the tissues between the toes.

Much has been written about the disorder, and my aim in this post is to briefly present the scientific facts and share with you my experiences as a professional hoof trimmer.

The term “foot rot” is used in this post, referring to its scientific name, Interdigital necrobacillosis.

What is the cause and what are the symptoms of foot rot?

Foot rot is a sudden and severe inflammation between the toes, most likely caused by the Fusobacterium necrophorum bacterium. This necro-bacillus (a germ that causes necrosis – meaning death of tissue) is always present in the environment. (Reference to Zoetis website)

It is commonly assumed that, under certain conditions, these bacteria are able to penetrate the skin between the toes, often through a small weakness or injury in the skin. The result is a reactive inflammation, often with a very rapid and severe onset. The swelling is centered above the claws and frequently on one foot only. It is not unusual to have more than one animal affected at the same time.

Proper and immediate treatment is essential to stop the infection process at this stage! Often a second stage develops in which also the interdigital space (the skin between the two claws) becomes inflamed with necrosis and pus. This causes a foul smell and results in a deep wound between the claws. As this deep type of wound heals, it will lead to excess growth, often referred to as a tyloma or corn.

A secondary symptom can be separation or detachment from the horn, like an “ingrown nail,” at which point we enter another stage. This irritation will cause more swelling and inflammation and before you know it, the P3 bone or pedal joint will be irreversibly damaged.

All of the above might seem rather overwhelming, but as a positive point, I’d like to add that foot rot doesn’t need to be a serious dairy farm problem. Before going over the treatment procedures, the following question should be addressed.

How can foot rot be distinguished from other hoof disorders?

If your cow has been lame for a long period of time, the cause most likely is not foot rot. The foot may smell and look “rotten,” but the inflammation is probably not caused by foot rot, and we’re dealing with another cause of lameness. (If it was foot rot, this would be the point where it has gone into a secondary stage and is now affecting more areas of the foot or leg. In this case, we have a mess that is not easily reversed. I’ll get to that later in this article.)

Early recognition and action is the key to proper diagnosing. I have created an easily downloadable hoof disease chart which contains the common hoof disease in cattle. This reference sheet can assist you with the diagnosis of hoof problems. The other hoof diseases and their differentiating factors can be broken down as follows:

If your cow has been lame for a long period of time, the cause most likely is not foot rot.

- A (complicated) sole ulcer, double sole, and white line defect are confusing and prone to be misdiagnosed under the name of “foot rot.” Holding on to the symptoms of foot rot: rapid onset (12-20 hrs), the “centered” swelling above the foot, combined with a slight fever and an often noticeable production drop, will help you in your judgment.

- Heel erosion, where the heel bulb or ball horn is being undermined and deep grooves are appearing in the rear of the foot, can also cause some misdiagnosis. There is often a foul smell, but the onset of lameness occurs over an obviously much longer period, and the lameness may not appear as severe. This defect affects the claws themselves, whereas foot rot appears “above” the claws, within the foot.

- Hairy heel warts (Digital Dermatitis or DD) are also confused with foot rot, mainly because of the severity of lameness and the strong foul odour. Still, when compared to foot rot, this condition only affects the outer skin, primarily in the heel area. The “centered” swelling might not be as obvious, but when you have a close look, you’ll find that the heel warts have an open “skin” problem and a “ring” of hairs on the outer circle. As a side note, I’d like to add that I’ve observed more than once that a hairy heel wart will cause the foot to be “weaker” and less resistant, making it more prone to foot rot.

- Foreign objects can often cause major swelling in a short time. I’ve seen o-rings, 5-inch nails, baler twine, electrical staples, wraps that are overdue, etc. All of these will cause swelling, foul odour, and sometimes “self-amputation” and are not classified under foot rot.

My new and revised Record Keeping Worksheet keeps track of your herd’s hoof trimming records with ease and precision.

Record Keeping Worksheet

What preventative steps can be taken to eliminate foot rot?

- Proper cleaning of the facilities is always a must, not only for hoof defects but also for other health issues. In particular, foot rot will not spread as rapidly between animals when the environment is clean. Weakening factors, such as hairy heel warts (DD) and heel erosion, are also kept under better control in a clean barn.

- Timely control, treatment of an affected animal, and removal of the affected animal from the herd are great ways to prevent the spread of disease to the rest of the herd.

- Spread dry lime or other commercial drying powders around the water troughs as a preventive measure. This is not a proven method, but it has some merit due to the fact that it dries the feet and controls the bacteria count in the area.

- Clearing up messy areas that have a lot of obstacles (rocks, nails, glass, and frozen dirt) is recommended to avoid injuries to the skin that can allow bacteria to enter the foot.

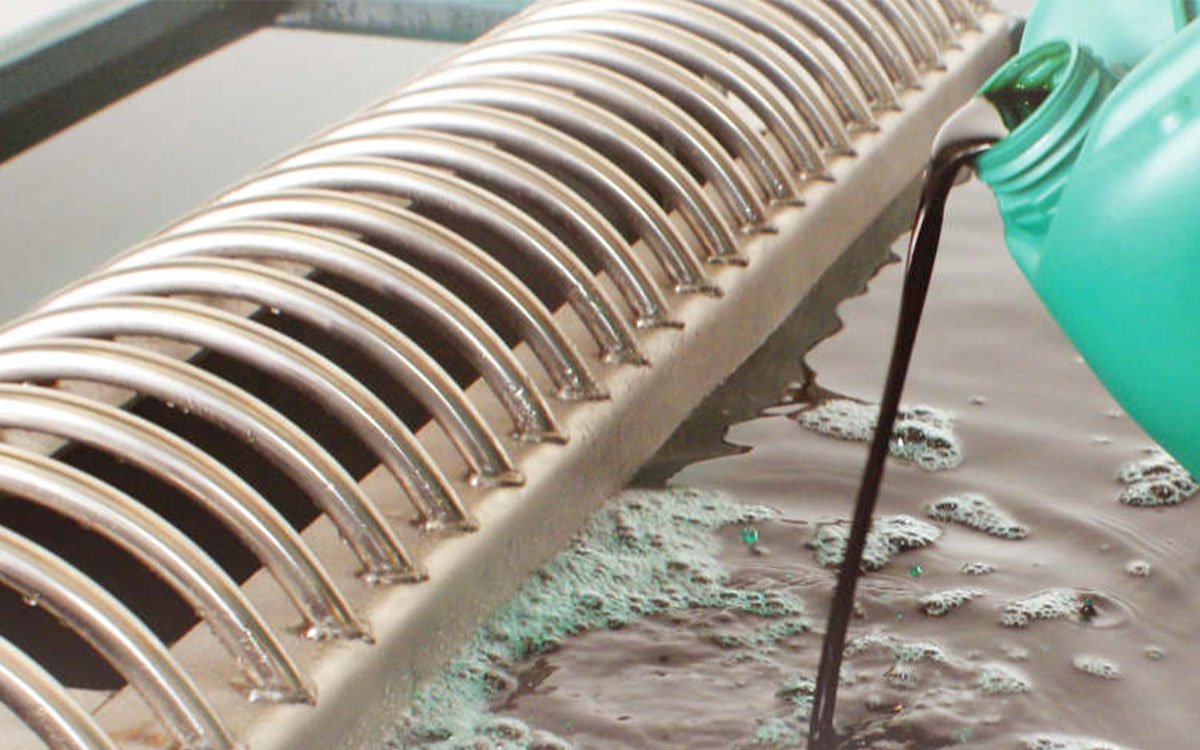

- Last but not least, the use of a foot bath as a preventive method is a valuable option to control not only foot rot, but a lot of other hoof diseases. Unfortunately, copper sulfate and formalin are still used on a lot of dairies, but these products are not environment-friendly and cause pollution. Formalin is also known to be a cancer-causing substance and should be avoided. Results accomplished with antibiotic-containing foot baths are limited due to the fact that resistance builds up; therefore, there won’t be a response after prolonged use. More producers are turning to other, safe alternatives with greater success. Also check out the Intra Bath, which has a triple purpose construction: a dividing grill to eliminate some manure pollution, a smaller volume that allows 35% less product to be used, and the extra length to allow more ‘dips’ for each foot.

This post is meant to be a quick guide for producers without difficult terms and explanations. Much has been written about hoof diseases and many books are available for the producer who would like to dive into this further. Please visit our hoof disease page to learn more about hoof diseases in dairy herds.